1. Introduction

Cerebral palsy is “A group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture causing activity limitation that is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing foetal or infant brain”

| [30] | Sadowska M, Sarecka-Hujar B and Kopyta I. (2020) Cerebral palsy: Current opinions on definition, epidemiology, risk factors, classification and treatment options. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 16: 1505. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S235165 |

[30]

. Cerebral palsy is the most common physical impairment in children globally, with a prevalence of 1.5-4 per 1000 birth depending on the region

| [18] | Khandaker G, Muhit M, Karim T, et al. (2019) Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in Bangladesh: a population‐based surveillance study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 61(5): 601-609. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14012 |

| [29] | Robertson CM, Ricci MF, O’Grady K, et al. (2017) Prevalence estimate of cerebral palsy in Northern Alberta: births, 2008-2010. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 44(4): 366-374. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.443 |

[18, 29]

. The prevalence in low income countries is higher than in high income countries because of higher poverty levels. The effects are also exacerbated by the lack of rehabilitation and educational services. These services are essential to improve the wellbeing and quality of life among those affected and can raise awareness among the community. The main types of cerebral palsy are spastic, athetoid, ataxia, flaccid and mixed types. Spastic cerebral palsy is the most common with 85% of children affected and has the highest risk of emerging secondary complications

| [15] | Jeffries L, Fiss A, McCoy SW, et al. (2016) Description of primary and secondary impairments in young children with cerebral palsy. Pediatric Physical Therapy 28(1): 7-14. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000210 |

[15]

. The main symptoms are related to movement and coordination due to weak muscles, uncontrolled movement, and muscle stiffness.

The diagnosis of cerebral palsy can be secured through brain scans such as magnetic resonance imaging, however, an argument around the appropriate age of diagnosis is still discussed among different researchers

| [35] | te Velde A, Morgan C, Novak I, et al. (2019) Early Diagnosis and Classification of Cerebral Palsy: An Historical Perspective and Barriers to an Early Diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 8(10): 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101599 |

[35]

. The earlier a child is diagnosed the faster an intervention can be started which improves function

| [23] | Morgan P and McGinley J. (2014) Gait function and decline in adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disability and rehabilitation 36(1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.775359 |

| [34] | Smithers‐Sheedy H, Badawi N, Blair E, et al. (2014) What constitutes cerebral palsy in the twenty‐first century? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 56(4): 323-328. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12262 |

[23, 34]

. Smithers-Sheedy et al. (2014) suggest that to be correctly diagnosed the child should be under four years old. Researchers indicate that in high income countries a diagnosis can be given at the age of 18-24 months, whereas in low income countries it can take up to five years for a final diagnosis

| [35] | te Velde A, Morgan C, Novak I, et al. (2019) Early Diagnosis and Classification of Cerebral Palsy: An Historical Perspective and Barriers to an Early Diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 8(10): 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101599 |

[35]

.

There is no cure for cerebral palsy, however, multidirectional approaches such as rehabilitation, psychological and social support improve function

| [37] | Trabacca A, Vespino T, Di Liddo A, et al. (2016) Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with cerebral palsy: improving long-term care. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare 9: 455. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S88782 |

[37]

. Pharmacological approaches usually include medication and surgery. Non-pharmacological interventions include allied health input such as occupational therapy to enhance independence

| [36] | Tessier D, Hefner J and Newmeyer A. (2014) Factors related to psychosocial quality of life for children with cerebral palsy. International journal of pediatrics 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/204386 |

[36]

. Allied health professionals might identify problems and negotiate plans to improve the wellbeing and quality of life for children. In recent years, assistive technologies have been effective in rehabilitation because these enhance independence and social participation

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[14]

.

Assistive technology is defined as ‘‘Any item, piece of equipment, or product system whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified or customized that is used to increase, maintain or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities’’

| [3] | Bausch ME, Mittler JE, Hasselbring TS, et al. (2005) The Assistive Technology Act of 2004: What Does It Say and What Does It Mean? Physical Disabilities: Education and Related Services 23(2): 59-67. |

[3]

. This is important in rehabilitation because such technologies increase confidence, independence, mobilization and participation which are crucial for the improvement of quality of life and wellbeing

| [9] | Gibson B. (2016) Rehabilitation: A post-critical approach: CRC Press. |

[9]

. In addition, such technology improves children’s function enhancing activities of daily living such as eating, dressing and walking. Assistive technology is also defined as special equipment, adaptive technology or assistive devices divided into two main groups: high and low assistive devices

| [10] | Gitlin LN. (2015) Environmental adaptations for individuals with functional difficulties and their families in the home and community. International handbook of occupational therapy interventions. Springer, 165-175. |

[10]

. High assistive devices are usually used in severe cases and include powered wheelchairs or augmentative and alternative communication systems. Examples of low assistance devices include pencil grips, orthoses, splints and walkers

| [39] | Zupan A and Jenko M. (2012) Assistive technology for people with cerebral palsy. Eastern Journal of Medicine 17(4): 194-197. |

[39]

.

The most common assistive devices for children with cerebral palsy are for mobility and communication needs

| [2] | Alqahtani S, Joseph J, Dicianno B, et al. (2021) Stakeholder perspectives on research and development priorities for mobility assistive-technology: a literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 16(4): 362-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1650300 |

| [20] | Lancioni GE, Singh NN, O’Reilly MF, et al. (2019) Assistive technology to support communication in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Current Developmental Disorders Reports 6(3): 126-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-019-00170-0 |

[2, 20]

. Mobility is essential for quality of life because this enhances independence, self-esteem, and is important for self-care, work and play

| [26] | Palisano RJ, Hanna SE, Rosenbaum PL, et al. (2010) Probability of walking, wheeled mobility, and assisted mobility in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 52(1): 66-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03388.x |

[26]

. Communication includes gestures and body language which enables the sharing of feelings, ideas and stories. Speech problems are one of the main comorbidities of cerebral palsy with 50% of children having speech impairments

| [7] | Darling-White M, Sakash A and Hustad KC. (2018) Characteristics of speech rate in children with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 61(10): 2502-2515. |

[7]

.

Assistive technology is seen as effective and important during interventions, therefore, an assessment of appropriate equipment depending on the individual skills and abilities is essential. The aim is to choose a device that will be motivational and meaningful for the individual

| [6] | Buitrago JA, Bolaños AM and Caicedo Bravo E. (2020) A motor learning therapeutic intervention for a child with cerebral palsy through a social assistive robot. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 15(3): 357-362. |

[6]

. The purpose of assistive devices is to enhance the ability of children with physical disabilities to function and to decrease the environmental barriers that limit achievement. Such devices can increase independence, social participation and quality of life

| [32] | Scherer MJ. (2005) Living in the state of stuck: How assistive technology impacts the lives of people with disabilities: Brookline Books. |

[32]

. It is essential to include the family in decision-making as parents often spend substantial time with their children and can encourage use of assistive technologies. It is essential too when deciding on a device such as a wheelchair to make sure it can easily, comfortably and safely be used

| [19] | Kirby RL, Rushton PW, Routhier F, et al. (2018) Extent to which caregivers enhance the wheelchair skills capacity and confidence of power wheelchair users: a cross-sectional study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 99(7): 1295-1302. e1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.020 |

[19]

. Parents should be trained in the use of the device to optimise its performance for their children

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

.

The researcher was keen to expand knowledge regarding cerebral palsy and the benefits of assistive technologies used in rehabilitation. As a result, a systematic review was conducted, the research question asked simply: what are the perceived benefits of assistive technologies in rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy, families and caregivers? The aim was to highlight the perceived benefits of assistive technologies from different perspectives including families and caregivers such as teachers and allied health professionals.

2. Method

The review was undertaken with a relativist ontological and constructionist epistemological position because of the researcher view that there are multiple realities lived and experienced by individuals shared and constructed across society

. The decision to conduct a systematic review stemmed from the researcher interest to evaluate the published evidence-base and analyze existing research in order to deepen understanding of the perceived benefits of assistive technologies for children with cerebral palsy, their families and caregivers. For this reason meta-ethnography was used following an interpretive approach which is a common form of qualitative research synthesis in healthcare

| [11] | Hannes K and Macaitis K. (2012) A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: update on a review of published papers. Qualitative research 12(4): 402-442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111432992 |

[11]

. Specifically, meta-ethnography translates concepts across studies to form third-order interpretations, or new themes, generating novel insights

| [31] | Sattar R, Lawton R, Panagioti M, et al. (2021) Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research 21(1): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w |

[31]

. Some consider meta-ethnography damages the original findings when generating new insights

, however the researcher was drawn to the deep, interpretive nature of this methodology to compare across studies and provide a line of argument expanded upon in the discussion below.

2.1. Data Collection

A systematic search was carried out via seven electronic databases: AMED, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL, MEDLINE, OTseeker, PubMed and SPORTDiscus. These were chosen because of their strong health-related focus. Search terms included cerebral palsy, assistive technology, assistive devices, adaptive technology, and rehabilitation, and were chosen with the help of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes (PICO) Strategy Tool which is the most commonly used tool for forming research questions

| [5] | Booth A. (2006) Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library hi tech. |

[5]

. The PICO’s purpose is to direct the researcher to identify the problem, intervention, and outcomes related to specific care issues

| [8] | Eriksen MB and Frandsen TF. (2018) The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA 106(4): 420. |

[8]

.

Academic and peer-reviewed articles were included to ensure high quality research enhancing the trustworthiness of the review

| [17] | Kelly J, Sadeghieh T and Adeli K. (2014) Peer review in scientific publications: benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. Ejifcc 25(3): 227. |

[17]

. Only qualitative articles in English published between 01/01/2009 to 20/03/2022 relating to cerebral palsy were included. The exclusion criteria included quantitative research, grey literature, systematic reviews, mixed-method studies, and studies relating to stroke, spinal cord injury, spina bifida and traumatic brain injury.

The total number of articles found was 386, duplicates were removed and the remaining articles were then screened. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) diagram below, see

Figure 1, shows the identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion criteria for the studies

. This led to nine articles included in the review, five were found via the databases and four through citation chaining.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

2.2. Data Extraction and Appraisal

The included studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool to identify strengths and weakness

, see

Table 1. At the same time data extraction began with consideration of the detail of each study, see

Table 2 for a summary. Meta-ethnography understands the original participant’s views in each study as first-order interpretations, whilst aware of these it was the second-order interpretation, that is the views of the researcher, that was mainly considered through repeated reading of the research.

2.3. Synthesis

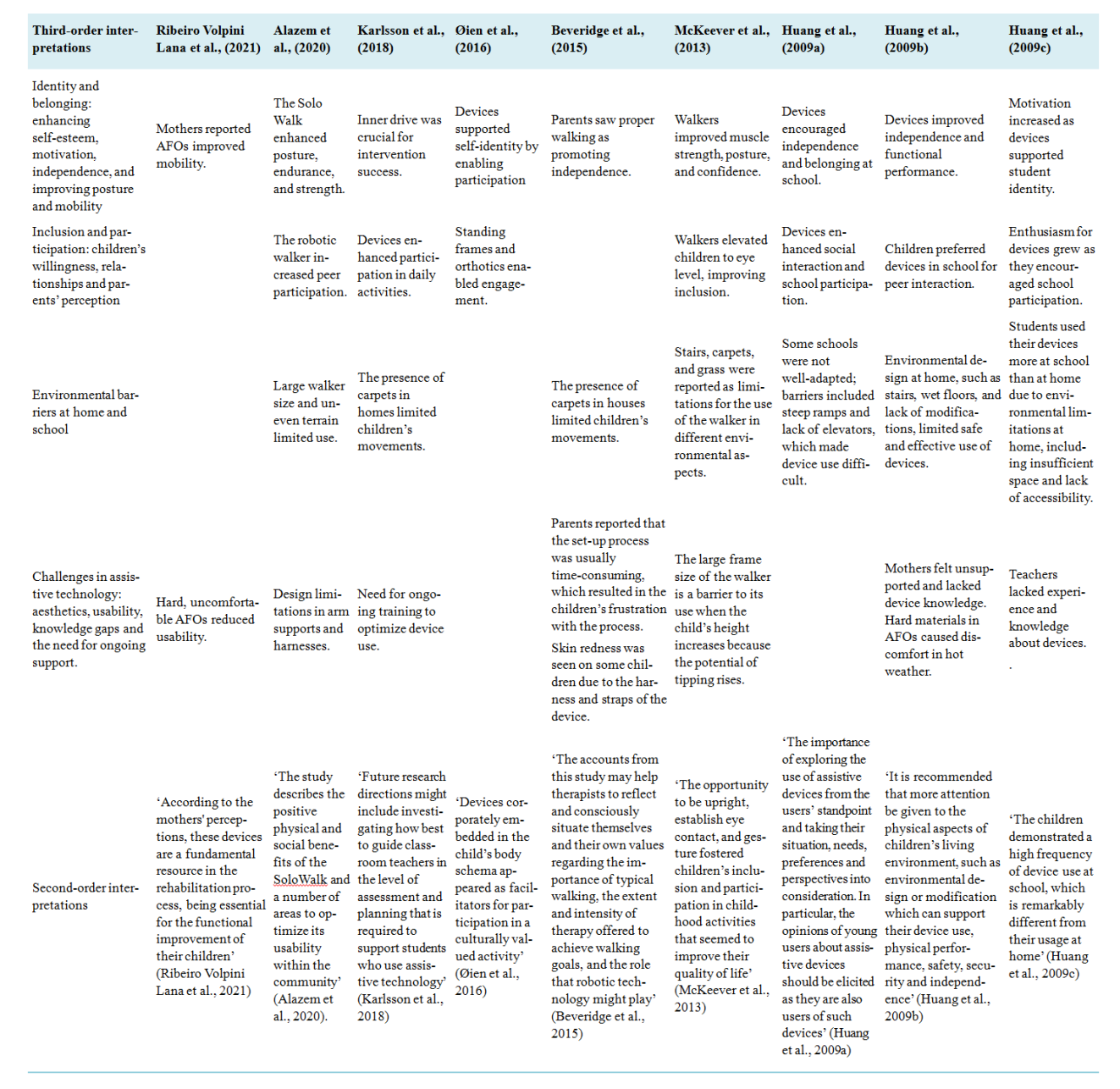

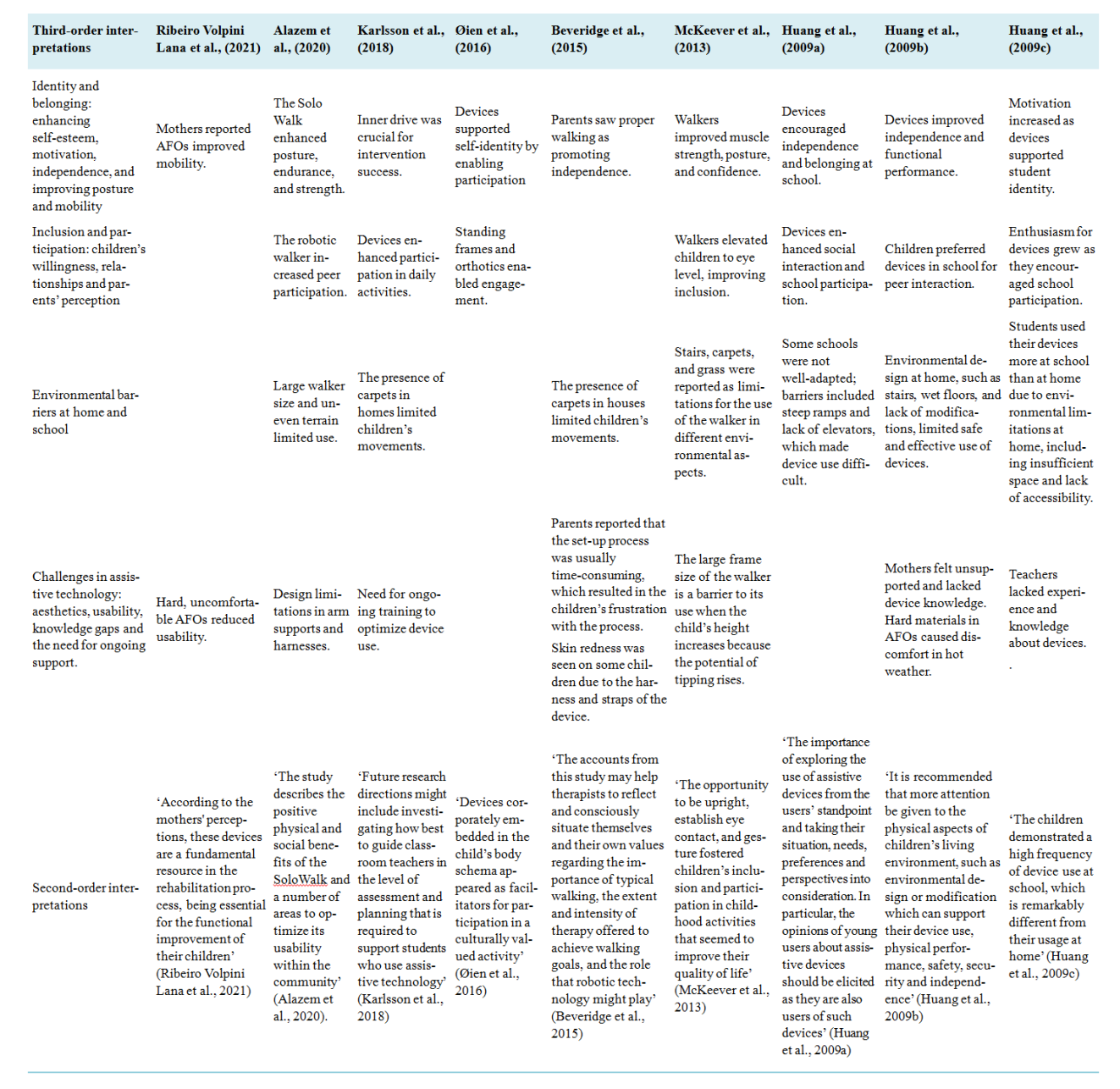

The process of synthesis was interpretive with words, phrases and themes relating to the included studies’ findings considered and reflected upon leading to the identification of commonalities and contradictions across the research. This showed how these related to each other and brought about a series of early concepts. A process of critical reflection helped to develop these concepts with close consideration of the second-order interpretations leading to an overall synthesis and third-order interpretations, see

Table 3. In meta-ethnography it is these third-order interpretations which provide novel insights, and which forms the structure of the findings below. The use of meta-ethnography has been seen especially in healthcare in recent years which influenced the design of this review

| [28] | Robart R and Boyle P. (2021) Supporting workers with lower back injuries to return to work: a meta-ethnography. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 84(2): 79-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022620958321 |

| [31] | Sattar R, Lawton R, Panagioti M, et al. (2021) Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research 21(1): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w |

[28, 31]

.

Table 1. CASP appraisal.

Criteria | Ribeiro Volpini Lana et al., (2021) | Alazem et al., (2020) | Karlsson et al., (2018) | Øien et al., (2016) | Beveridge et al., (2015) | McKeever et al., (2013) | Huang et al., (2009a) | Huang et al., (2009b) | Huang et al., (2009c) |

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

How valuable is the research?* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 2. Summary of included studies.

Author and country | Aim | Design | Participants | Findings | Strengths and limitations |

Ribeiro Volpini Lana et al., (2021) Brazil | To explore mothers’ insight of children with cerebral use regarding their children’s ankle-foot orthosis. | Semi-structured interviews | 24 mothers of children with cerebral palsy | 3 main themes emerged with 2 subthemes each: Benefits of the orthosis Improvement in positioning and mobility Prevention of deformities The orthosis in the child’s life The orthosis use in different environments The orthosis usage period What if it were like this Predilections and aesthetic suggestions about the orthosis Usability and practicality of the orthosis | Aim and methodology: the aim of the study was clearly stated at the beginning of the study. Interviews were conducted which is an opportunity for the participants to expand on their opinions. A limitation of the study is that it included only mothers whereas fathers’ perspectives were not taken into consideration. Recruitment strategy: no specific information on how participants were recruited. Relationship of authors and participants: all 3 researchers created the themes together, although 2 of them were familiar with the participants and had knowledge about their daily routine which may cause bias. |

Alazem et al., (2020) Canada | To identify the benefits and challenges of the use of SoloWalk in youth and young adults with cerebral palsy | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | 5 participants | 4 themes emerged with subthemes for each Physical advantages Social advantages Physical disadvantages Social disadvantages | Aim and methodology: the aim and methods were clearly stated in the study. A mixed method approach that included observation and focused group discussion was appropriately justified. Recruitment strategy: clear overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for recruiting participants. Ethical consideration: ethical approval was taken from all participants including the healthcare professionals which included a range of professions. Findings and data collection: the study included only 5 participants which may cause issues regarding the credibility of the findings. There was an unequal sex ratio of 4 males and 1 female in the study. The study included diverse cerebral palsy types, however, it included only GMFCS IV, therefore the findings can’t be generalized. The findings demonstrated both advantages and disadvantages of the robotic walker. |

Karlsson et al., (2018) Australia | To understand what factors affect assistive technology use in the classroom from teachers, allied health professionals and students with cerebral palsy and their parent’s point of view | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | 6 classroom teachers 6 parents with their children with cerebral palsy 16 allied health professionals | The findings addressed the domain of the international classification system included: Mental functions General tasks and demands Support and relationship Services, systems and policies | Aim and methodology: the study aim was clearly shown especially since it included different perspectives from different stakeholders. Teachers and allied health professionals were included in addition to students with cerebral palsy and their parents. Ethical considerations: ethical approval was obtained and informed consent was given with an explanation of the right to withdraw anytime. However, confidentiality and anonymity were an issue in the study. Data collection: all 6 teachers were only female and among the allied health professionals, there were 15 females and only one male. All interviews and focus group discussions were audio-recorded which allows for later analysis with all the researchers. Findings: the findings focused on the international classification system framework which demonstrated both enablers and barriers seen by different stakeholders regarding assistive technology use in the classroom. |

Øien et al., (2016) Norway | To understand the children’s experiences regarding assistive technology devices as social-cultural objects in schools. | Observation and interviews | 9 children | Exacerbate disability Enhance selfhood Embodied capacities and participation | Aim and recruitment strategy: the study focused on the children’s perspective, as usually studies focus on the parent and teachers’ opinions. There was a mix of sex ranges which was composed of 4 girls and 5 boys. It included children with cerebral palsy that are cognitively impaired or have speech problems. Findings and data analysis: the findings of the study were not clearly stated and the researcher didn’t describe or give sufficient information on how the data was analysed. |

Beveridge et al., (2015) Canada | To identify parents’ values regarding walking with their perceptions of robotic gait training and how parents’ insights about walking affect therapy decisions for their children | Semi-structured interviews | 5 parents | Three themes: Parents valued walking as a key component of their child’s well being Robotics were pursued as the ‘next best thing’ in therapy Parents sought to maximize the amount and variety of their child’s therapy | Aim and methodology: the purpose of the study was clearly stated. Semi-structured interviews were chosen to explore parents’ experiences which allows for deep expansion of their feelings through interviews. Interview questions are shown in the study to show the robustness of the study. Recruitment strategy: the sample was small it included 5 parents and it focused on spastic cerebral palsy of GMFCS level II, therefore results can’t be generalized. The participants were recruited through randomized control trials and they were volunteering. Parents who volunteer to participate in randomized control trials need time commitments and with volunteers participating it may not present the typical parents. Findings: the findings were explained how it was analysed clearly and robustly with statements included from the interviewees. |

McKeever et al., (2013) Canada | To explore parents’ reflections regarding their children’s hands-free walker device use. | Structured open-ended interviews | 20 participants | 4 themes: Bodily function, position, and comportment Communication Participation and inclusion Freedom and independence | Ethical and relationship between researcher and participants considerations: the participants were a mix of the gender both female and male all participants were given informed consent. The researchers were the ones that conducted the interview with the participants. Findings and data collection: the interview questions were not included in the study to show their robustness, but they were audio-taped and transcribed for analysis. The researchers had team meetings to verify the codes to emerge appropriate themes. The findings were clearly stated in the study. |

(Huang et al., 2009a) Taiwan | To understand the use of assistive devices in school and home settings from children’s experience. | Semi-structured interview | 44 participants 15 children 15 mothers 14 teachers | 4 themes: Children’s perception of cerebral palsy Children’s perceptions of assistive devices Children’s attitude toward device use at home and school Factors influencing the children’s device use at home and school. | Aim and methodology: the study aim was clearly written. Semi-structured interviews were used which allows the participant to share their experiences. Ethical consideration and data collection: informed consent and confidentiality were obtained in the study and the interviews were audio-recorded. Findings: the findings were demonstrated clearly. The parent’s participants were all mothers which limited the findings regarding the father’s experiences, although the children were girls and boys. |

Huang et al., (2009b) Taiwan | To identify the factors affecting the use of assistive devices in the home setting mainly from the children’s point of view. | Semi-structured interview | 30 participants 15 children 15 mothers | 4 themes: Children’s reluctance Mother’s perspective Physical environmental barriers Device-related barriers | Aim and methodology: the study aims and method used were clearly stated in the study. Semi-structured interviews were used both with the children and mothers separately to provide deep conversations. Ethical consideration: no ethical considerations or informed consent was mentioned in the study. Data collection: the children participant were a mix of girls and boys and a range of the GMFCS of level I-IV. A limitation of the study was that only mothers were included as they were seen as the main caregivers of their children. The interview was conducted in Mandarin, and it was carefully translated to English, therefore all researchers took part in the data analysis. Findings: the findings were clearly stated with convenient quotations from the participants sharing their perspectives and what factors are mainly affecting their device uses at home. |

Huang et al., (2009c) Taiwan | To explore the use of the devices in school and identify the factors linked to devise utilization from a children’s insight. | Semi-structured interview | 44 participants 15 children 15 mothers 14 teachers | Five themes: Children’s willingness Teacher’s attitude Mother’s support Physical environmental factors Device-related features | Aim: The aim was clear in the study focusing on the children’s experiences in addition to teachers and parents. A range of sex and GMFCS levels was seen in the study. Ethical consideration: no ethical consideration was mentioned in the study. Teachers were a mix of females and males, although for guardians only mothers were included. Findings: the findings were clearly analysed with the inclusion of all authors. |

Table 3. Summary of concepts linking with second and third-order interpretations.

3. Findings

3.1. Identity and Belonging: Enhancing Self-Esteem, Motivation, Independence, and Improving Posture and Mobility

The impact of the use of assistive devices was seen in many of the studies where children created their identities and had a sense of belonging. Through the use of the devices they became part of the child and in some cases part of their character. A study by Øien et al. (2016) conducted an interview with children aged 5-6 focusing on the identity the child is becoming. One of the participants during an interview was shown a picture of himself taken a year before while using one of the devices. The interviewer used a different term than what the participant used and the child was annoyed that the device was referred to differently. It seems devices children use is important because it becomes part of their identity.

In relation to the use of a walker McKeever et al. (2013) emphasized the use of this heightened children’s sense of belonging. Five parents highlighted that when their children used walkers they felt increased belonging to their peer group. One of the mothers reported that the walker made her son more acceptable among his peers. Additionally, seven of the parents reported that the walkers increased the confidence of their children. These raised the user’s eye level with siblings and peers which enhanced confidence and motivation. One of the parents reported:

He seems to have a lot more confidence in, ah, talking to people his own age, siblings and, ah, that sort of thing.

In the research by Huang et al. (2009a; 2009b) the children reported that with the support from their teachers and peers in school they had increased levels of confidence. They became aware that special features of their character can impacted on their peers. One of the children reported:

I have two good friends. They started to help me in Year 4. Therefore, we had the opportunity to know each other and later become good friends | [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

Many children are more motivated to use their devices in school rather than at home because these allow for strengthening peer relationships and socialization. One child reported:

At school, I don’t like my parents’ help. I want to learn how to do all the things by myself, like everyone else does, even if I have to do them by using my devices | [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

.

In Karlsson et al’s (2018) study, students’ motivation and inner drive were seen as important for device usage in school. Furthermore, these help children to fulfil their student role (Huang et al., 2009c). However, at home the experience differed as children enjoyed being in a natural and intimate space receiving assistance from family members. Therefore, it seems motivation is reduced when at home compared to school

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

. One child admitted:

I am lazy. I want to live at will at home, and I am accustomed to [others’ help] | [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

The main purpose of assistive devices it seems is to increase the independence. The feeling of having the freedom and choice of where and what you are interested in achieving is crucial in an individual’s life. Alazem et al. (2020) focused on a robotic walker which allowed independence in movement. Being independent allows improvement in functional activities of daily living such as dressing, toileting and walking. It improves the quality of life for the users enabling them to achieve their goals independently.

According to

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

[4]

robotic gait training decreases falls and enhances independence McKeever et al. (2013) found that 50% of parents reported that the use of a hands-free walker gave their child the feeling of being independent. The parents stated that the walker increased their children’s mobility resulting in greater freedom and a feeling of independence. According to Huang et al. (2009a; 2009c) several children indicated that with the devices their independence improved. One of the children reported:

At school, I don’t like my parents’ help. I want to learn how to do all the things by myself, like everyone else does, even if I have to do them by using my devices | [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

Riberio Volpini Lana et al. (2021) focused on the use of an ankle-foot orthosis (AFO), which aims to improve foot positioning and prevent muscle shortening. These improve function, strengthen the lower limb, supports standing and begins the process of starting to walk. Two mothers shared their opinion regarding these:

With it (the orthosis), he can have better posture, better structure in his foot…

…The orthosis greatly favored the fact that can stand.

The parents emphasized that the ability of walking was seen as crucial for the children’s wellbeing (Beveridge et al., 2015). The importance of correct walking was emphasized from the father’s perspective as follows:

The walking pattern is very important... Because Sam could walk... by himself. But not correctly. So the best and correct walking style is very important for Sam and us.

In the McKeever et al. (2013) study the intervention was through the use of a hands-free walker. This made a significant change in the posture and uprightness of the children from the parent’s view. Many parents reported that their children’s muscle strength was developed and flexibility was improved. One of the mothers reported:

So I would say benefits are that she is upright and moving and using more mus … you know, muscle groups and, ah, it’s a good workout for her.

3.2. Inclusion and Participation: Children’s Willingness, Relationships and Parents’ Perception

Most children accepted their devices because they have used these from a young age. As they mature they realize that the use of the devices could be beneficial not only functionally but also in other areas such as socialization

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[14]

. Several participants reported that their participation and social interaction in school settings had improved while using the devices

| [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

[12]

. One of the participants said:

My relationships become better because I can play with other children with the help of the devices. Without the devices, I can’t play with them or join in a game with them. Maybe, I will then lose some friends.

Huang et al. (2009c) highlighted that many children preferred using their devices in school compared with other places such as the home or in the community. It gave them higher motivation to use their devices to socialize and participate with peers. To feel included in the community is an important aspect for users. Devices such as walkers have allowed children to feel included and have a sense of belonging. These increase self-esteem and confidence which improves participation and social interaction. One child reported:

Amongst all the devices I have, my favourites are the bicycle and the walker. I like my walker most, because I can play with others when using it....Although walking with the walker is very tiring for me, I still enjoy it, because I like to play with the other children.

Social participation is viewed as necessary for children’s development and learning

. In this study during observations and interviews with children it was realized that the use of different devices improved social participation. It seems also that such devices increase the opportunity for independent walking further enhancing social participation

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

[4]

.

Parents realized that there are many improvements with the use of assistive devices. McKeever et al. (2013) focused on the use of a hands-free walker and it seems children’s communication abilities improved enhancing participation with peers. One of the parents reported:

You know one thing I notice when she is in the walker is, she talks more. Like she doesn’t … she doesn’t talk, but – like in words, but she’s much more verbal once she’s in her walker.

In addition eye contact improved with seven parents emphasizing that the walker gave their child the ability to be on the same eye level as siblings and friends

| [21] | McKeever P, Rossen BE, Scott H, et al. (2013) The significance of uprightness: Parents’ reflections on children’s responses to a hands-free walker for children. Disability & Society 28(3): 380-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.714259 |

[21]

. This enhanced participation with others and boosted children’s confidence. One of the parents noted:

It’s just made her so happy to, ah, be able to be upright and look her friends in the eyes. It just gives her that sense that she’s on even footing with her buddies and I don’t know that she would have had that without the walker.

3.3. Environmental Barriers at Home and School

It seems there are many challenges that children and their families experience in relation to securing a preferable and secure environment to use devices to provide the best outcome. Riberio Volpini Lana et al. (2021) highlighted different views regarding AFO usage in different environments. One mother commented that her daughter uses orthosis only in school and rehabilitation.

She uses it more to go to school and to come to the AMR (Rehabilitation Center).

Another mother reported that their child uses the orthosis in all environments except for school.

I remove the orthosis for him to go to school. [...] He already uses it to go to Physiotherapy.

A reduction in the use of assistive devices in the home is evident for many children and young adults because of environmental barriers

| [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[12-14]

. Children used their devices in school more than at home, and many devices were abandoned. The large size of devices, such as the robotic walker, is one of the main issues faced by children with any houses often limited in space which challenges the use of devices in the home setting.

McKeever et al. (2013) reported that seven parents had to adapt their home to be accessible for different devices used by their children. Some children expressed their preference for living more naturally without the use of devices at home because they can live in the manner they wanted. They would also be dependent and get more assistance from family members, although in school their preference would be to use their devices as this had a positive effect in terms of participation with peers. The children reported higher motivation to use the devices in school therefore because these provide more opportunities to socialize.

Huang et al. (2009b) reported that even though mothers viewed the devices as being helpful and effective they did not give their children sufficient encouragement to use these at home. They considered their assistance was safer and more practical as not all houses are modified for their children’s needs. Additionally, mothers were worried that their children would have negative experiences while using the devices at home because of barriers, limiting usability in many cases. It seems the limited space at home reduced the use of the devices compared to school. One of the mothers reported:

The major problem for [my daughter] to use her walker is that our space is not large. But manipulating the walker basically requires a big space. This usually inconveniences other households and they have to be very careful when passing by her

Children use their devices more in school than at home, however barriers in some schools exist limiting device use. McKeever et al. (2013) highlighted a limitation regarding walker manoeuvrability and children becoming frustrated with steering and turning this. One parent said:

I think mainly for her it’s … where she would get stuck, like run into a wall or like, say, get frustrated because she can’t get herself out of it. Like she can’t back up or something.

Huang et al. (2009a) reported on environmental barriers such as steep ramps, wet floors and lack of elevators in some schools. Many schools were significantly adapted for a range of device users, however other schools needed further modification to be safe. Some devices were inappropriately designed for use in classrooms which affected the children’s function

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[14]

. Many schools adapt and make use of the environment to enhance access for a range of devices used by children, for example by providing classes on the ground floor or near elevators and making sure that toilets are not wet or slippery.

3.4. Challenges in Assistive Technology: Aesthetics, Usability, Knowledge Gaps and the Need for Ongoing Support

Mothers’ perspectives regarding design of AFOs were similar, most agreed these lacked paediatric design and suitable colours

| [27] | Ribeiro Volpini Lana M, Pimenta Maia J, Horta AA, et al. (2021) 'What if it were like this?' Perception of mothers of children with cerebral palsy about the ankle-foot orthosis of their children: A qualitative study. Child: care, health and development 47(2): 252-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12828 |

[27]

. One mother reported:

If they would only change the colours. I've seen some animal imprints/decals, I found them very cute!

The usability of the AFO was also highlighted as hard, uncomfortable and unbreathable. One mother noted her opinion with some suggestions:

I think it's very hard. It should be softer. I would put some foam inside.

It's very hot, I would change something to make it more breathable.

Robotic walkers provide benefits but there are disadvantages too

, in this study young people shared their thoughts regarding the device which is seen as large in size requiring substantial space which was not always available in all settings. The design of the harness, arm supports and handles limited use of the device and additional padding and a circular design for the leg straps was suggested. Some participants considered the device aesthetically pleasing while others wanted a more attractive design including more colour. One patient commented:

Maybe if it came in different colours like purple, rainbow or camouflage.

The Lokomat gait training device was reported by many parents that the set-up process was time-consuming frustrating use by the children

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

[4]

. In addition, many children complained of skin redness and soreness due to the device’s straps

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

[4]

. In McKeever et al’s (2013) study parents reported their experiences regarding a hands-free walker, one of the issues highlighted was the manoeuvrability difficulty which resulted in frustration during turning and steering, further the walker is large in size and when a child’s height increases the possibility of tipping increases.

Huang et al. (2009b) reported on different devices that were used by participants in the home. Although assistive devices in general are more beneficial than harmful, they can cause skin irritations and pain. Wheelchairs made with material with poor breathability can cause stickiness around children’s backs when sitting for extended periods. Children reported use of AFOs brought about abrasions and blisters. Additionally, it was noted that AFOs are made from hard material which results in an uncomfortable and unbreathable device that can cause pain to some users. One of the mothers reported:

A big problem for [her] in wearing AFOs is that her skin is easily damaged. Maybe because she has poor circulation in her legs or because she always sits the whole day without enough exercise, the skin on her feet is very delicate and she easily suffers lesions, in particular on her toes. Once she hurts her toes, they only recover slowly. This problem is extremely serious in the summer because the weather is hot. Even though she wears sandals now, this situation does not improve.

There seems to be some perception of limited knowledge of parents and the lack of support and training for caregivers including teachers and allied health professionals. Mothers highlighted their lack of understanding of devices

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

. Many mothers reported the limited advice they were given about devices, additionally they reported not receiving sufficient introduction or follow up information which resulted in not having a clear understanding of the function of the device. The need for training was mainly realized when facing a problem regarding a device and not knowing how to solve the problem resulting in a reduction in encouragement to children to use devices at home.

Furthermore, teachers and allied health professionals were not given sufficient training and support about device use and children’s progression

| [16] | Karlsson P, Johnston C and Barker K. (2018) Influences on students' assistive technology use at school: the views of classroom teachers, allied health professionals, students with cerebral palsy and their parents. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 13(8): 763-771. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2017.1392622 |

[16]

. Interviews and focus groups with teachers, allied health professionals, students and parents were carried out to find out about assistive technology use in schools. This highlighted the need for ongoing support and training for caregivers. According to one allied health professional:

We often see children who can operationally use their devices beautifully but people around them … actually don’t know the functional pragmatics of how to use their device.

Time was the main barrier faced by caregivers, as an allied health professional commented:

I think everybody’s so time poor, therapists and teachers, that there’s not that adequate communication perhaps with all relevant parties about how something should be used.

The long waiting lists for trialling or training on a specific device resulted in frustration among teachers and allied health professionals. In addition, allied health professionals realized that teachers sometimes found it difficult to understand the purpose of the device. One allied health professional reported:

I think the teachers don’t often see the link between the individual education plan and the use of technology.

Therefore, support and training are important. Many teachers reported that they did not receive the skills and training required which resulted in abandoning devices within the school environment. The need for ongoing support was highlighted, one allied health professional commented as follows:

The technology doesn’t actually take a person from being disabled to being equally able to their peers so there still needs to be other supports in place and ongoing support… So how much the gap the technology actually bridges is really important.

Parents and allied health professionals reported the lack of clear guidelines regarding costs and collaboration between organizations. As a result, inconsistency appears regarding the availability of training. This lack of training and support reduces confidence and causes users and those who support them to feel uncomfortable with the provision of new devices, especially as the child’s needs change. Huang et al. (2009c) shared the experiences of teachers regarding device usage in schools with their students. The devices are seen as beneficial for a child’s development which enhances achievement, however, many teachers highlighted the need for ongoing training because their knowledge of the devices was limited. Mainstream teachers seem to be unskilled with assistive devices and lacked experience in managing these. They gradually learned on their own how to operate the devices because of their daily interaction with the children. Additionally, many teachers reported not having sufficient training with special educational needs because they were trained as mainstream teachers. This resulted in affecting the children’s understanding of their assistive devices due to the limited experience of the teachers. The teachers highlighted the lack of interdisciplinary collaboration between other professions which resulted in insufficient opportunities to deepen understanding on the use of the device.

4. Discussion

This review was conducted to explore the literature regarding the benefits of assistive technologies in rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy, families and caregivers. The aim was to identify the benefits of assistive technologies from different perspectives including families and caregivers such as teachers and allied health professionals. A line of argument now follows that understands the findings as providing two advantageous third-order interpretations and two highlighting barriers in relation to assistive technology.

Assistive devices aim to improve the quality of life, motivation, wellbeing and social participation of children with cerebral palsy, therefore increasing confidence, mobilization and motivation for participating and socializing

| [21] | McKeever P, Rossen BE, Scott H, et al. (2013) The significance of uprightness: Parents’ reflections on children’s responses to a hands-free walker for children. Disability & Society 28(3): 380-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.714259 |

[21]

. Assistive devices have increased inclusion and participation among children with cerebral palsy with their peers and other family members too

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[14]

. Social participation is seen as crucial for development and learning

. Additionally, this increases independence which enhances quality of life by being better able to perform activities of daily living

| [1] | Alazem H, McCormick A, Nicholls SG, et al. (2020) Development of a robotic walker for individuals with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 15(6): 643-651. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1604827 |

| [27] | Ribeiro Volpini Lana M, Pimenta Maia J, Horta AA, et al. (2021) 'What if it were like this?' Perception of mothers of children with cerebral palsy about the ankle-foot orthosis of their children: A qualitative study. Child: care, health and development 47(2): 252-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12828 |

[1, 27]

.

Mobilization and especially walking is understood as a crucial aspect of an individual’s wellbeing and self-esteem

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

[4]

. Being able to walk improves social participation between peers because people can move freely. Many parents recognised their children’s improvements in communication due to the use of assistive technologies which has a beneficial impact on quality of life and participation

| [21] | McKeever P, Rossen BE, Scott H, et al. (2013) The significance of uprightness: Parents’ reflections on children’s responses to a hands-free walker for children. Disability & Society 28(3): 380-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.714259 |

[21]

. To continue benefitting from the assistive technologies for children with cerebral palsy improved collaboration between different providers seems to be needed. Families, teachers and therapists are important, however, other external users can influence progress. Collaboration between statutory services such as education and health is necessary combined with progressive developments in housing and broader society to enhance access.

The use of assistive devices in the school environment is higher than in the home for several reasons. Firstly, use in the school strengthens peer relationships and socialization, therefore, children are more motivated to use such technology

| [12] | Huang I-C, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009a) Children's perceptions of their use of assistive devices in home and school settings. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802613701 |

[12]

. Secondly, some homes are not accessible for effective use of assistive technologies which challenges the use of devices at and reduces motivation

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

. Additionally, the lack of knowledge and ongoing support for families reduces the motivation to use assistive technologies, which negatively impacts on the performance of the children. Arguably this frustrates the rights of the child and inequality increases as a result.

It seems many homes are not adapted sufficiently resulting in environmental barriers for device use in the family home. Large devices such as robotic walkers can be difficult to use within the home due to limited space

. Many homes need minor adaptation such as removing carpets and furniture, but for others, it can become be more complex. Some parents consider their personal assistance is safer than reliance on assistive technologies due to low education and awareness regarding devices

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

. Parents spend considerable time with their children, therefore, they are best positioned to encourage use of devices. When parents lack confidence regarding devices they are less inclined to encourage and motivate their children to use these which can impact child development. Mothers highlighted the lack of support and insufficient orientation or follow-up of devices

| [13] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009b) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: factors influencing the use of assistive devices at home by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(1): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00898.x |

[13]

. For example, the set-up process of some devices was reported by many parents to be complex and time-consuming causing frustration. Some walkers’ manoeuvrability was seen as difficult which resulted in frustration during turning and steering. These are some of the challenges reported by children and their families that can reduce the use of devices. It is important therefore that a family-centred approach is followed during rehabilitation which includes the parents in decision-making thereby enhancing the quality of life and wellbeing of children.

Teachers and allied health professionals highlight insufficient training and support regarding devices

| [16] | Karlsson P, Johnston C and Barker K. (2018) Influences on students' assistive technology use at school: the views of classroom teachers, allied health professionals, students with cerebral palsy and their parents. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 13(8): 763-771. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2017.1392622 |

[16]

. Many teachers stated that they neglected devices because they were not sufficiently trained. The need therefore for ongoing support is important for all caregivers to improve the wellbeing and quality of life of children in such settings. In addition, teachers reported a lack of engagement and collaboration with other professions

| [14] | Huang IC, Sugden D and Beveridge S. (2009c) Assistive devices and cerebral palsy: the use of assistive devices at school by children with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development 35(5): 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00968.x |

[14]

. Teachers and therapists are likely to need specific training to enhance the benefit of such devices for users. Each specific assistive device has its benefits and is operated differently, therefore, the need for knowledge of each device and good communication between children, families and caregivers is necessary. As devices develop and new technologies are used, it is important to regularly review developments and updates to provide the best outcomes for children, their families and caregivers. Such training could include theoretical and practical learning and workshops. Further research relating to increasing awareness and education among children, parents and caregivers is recommended. Most studies are conducted in high-income countries, specific research therefore to understand the experience and perspectives of participants using assistive technologies in low-income countries is also recommended.

The strength of this review is that it included the experience and perspectives of children, families, teachers and a range of professionals including occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech pathology, teachers, physiatrists and engineers. A limitation might be that the included studies seem to highlight the experience and perspective from females mainly due to prevalence of mothers as caregivers and women as teachers

| [4] | Beveridge B, Feltracco D, Struyf J, et al. (2015) “You gotta try it all”: parents’ experiences with robotic gait training for their children with cerebral palsy. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics 35(4): 327-341. |

| [16] | Karlsson P, Johnston C and Barker K. (2018) Influences on students' assistive technology use at school: the views of classroom teachers, allied health professionals, students with cerebral palsy and their parents. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 13(8): 763-771. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2017.1392622 |

| [21] | McKeever P, Rossen BE, Scott H, et al. (2013) The significance of uprightness: Parents’ reflections on children’s responses to a hands-free walker for children. Disability & Society 28(3): 380-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.714259 |

| [27] | Ribeiro Volpini Lana M, Pimenta Maia J, Horta AA, et al. (2021) 'What if it were like this?' Perception of mothers of children with cerebral palsy about the ankle-foot orthosis of their children: A qualitative study. Child: care, health and development 47(2): 252-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12828 |

[4, 16, 21, 27]

.